BMW’s EV Journey: From the 1972 Elektro 1602 to Neue Klasse

No car company wants regulation. But every so often, rules and deadlines force the industry to move in ways it might not otherwise. For BMW, California’s first emissions standards in 1966 and the U.S. Clean Air Act in 1970 were just that kind of push. They didn’t just clean the air — they accelerated BMW into fuel injection with cars like the 2002 tii, making them cleaner, more efficient and quicker.

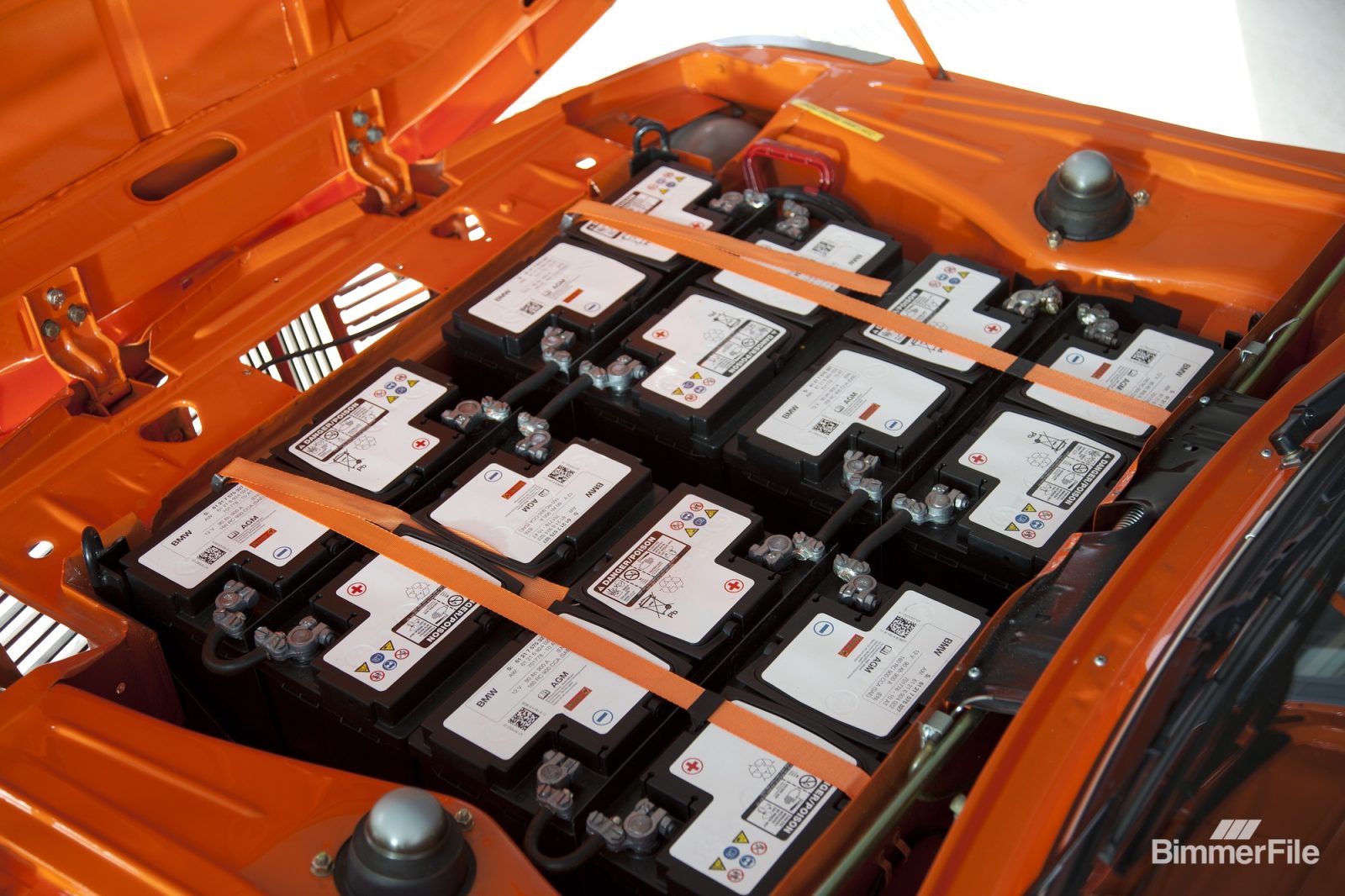

But lowering emissions was only part of the story. Eliminating them completely required something radical: a return to electric drivetrains. And while BMW wasn’t building cars during the first “electric age” at the turn of the century, it dipped its toes in 1972 with the Elektro 1602, a converted 2002 that quietly paced marathon runners at the Munich Olympics. Twelve lead-acid batteries and a 44-mile range meant it was more science project than production car, but it marked the beginning of a long journey.

Through the 1980s and 90s, BMW chased hydrogen as a zero-emission path while regulators in California kept pressing for EVs. Concepts like the E1 and E2 looked futuristic but struggled with sodium-sulfur batteries. Even a small fleet of 3 Series with experimental range-extenders missed the mark. The reality, as BMW NA’s Rich Brekus later put it: “The E36 electric vehicles were terrible.”

California eventually agreed to accept BMW’s Partial Zero Emission Vehicles instead — cars that were still gasoline-powered but extraordinarily clean. Millions of them hit the road, dramatically improving California’s air quality.

By 2007, BMW shifted gears. Cancelling its F1 projectm, BMW shifted engineering talent to electrification. This combined with hydrogen experiments being abandoned, the company launched Project i. The idea wasn’t just to build an EV, but to rethink mobility in the age of megacities. Enter the MINI E: 1,088 lithium-ion cells powering a MINI hatch stripped of its rear seats. With 201 hp and a claimed 156-mile range, it was crude but promising.

What made the MINI E remarkable wasn’t the hardware but the test program. In 2009, BMW put 450 of them in the hands of real customers in LA, New York and New Jersey. Leasing cost $850 a month, and drivers had to provide feedback. Suddenly BMW wasn’t just experimenting in a lab — it was living the EV future alongside its customers.

Enthusiasts like Pacific Palisades resident Peter Trepp blogged daily about charging, regenerative braking and life without gas stations. Customers discovered the joys (instant torque, one-pedal driving) and the headaches (European plugs without UL approval, brutal range loss in the cold).

Phase two came in 2012 with the BMW ActiveE, a battery-electric 1 Series coupe with liquid-cooled batteries and more refinement. Range was still only about 100 miles, but the car previewed the powertrain and thermal management that would underpin BMW’s first true production EV, the i3.

The MINI E and ActiveE weren’t sales hits — they were rolling test beds. But they taught BMW how customers charge, what range anxiety feels like, and how utilities might one day use EVs to stabilize the grid. They also laid the groundwork for BMW’s circular economy thinking, repurposing old EV batteries for stationary energy storage.

And while Tesla grabbed headlines with the Model S and its 300-mile range, BMW’s methodical path through Project i showed how a legacy automaker could learn by doing. The experiments were messy, sometimes frustrating, but essential.

Looking back, the MINI E and ActiveE feel like scrappy prototypes compared to the polished Neue Klasse EVs about to arrive. But they were the spark. Regulation may have forced BMW’s hand, but what kept the momentum going was curiosity, engineering stubbornness and the willingness to hand imperfect cars to real drivers. Without that, there’s no i3, no iX, and no EV future for BMW and no forthcoming Neue Klasse.